“Give us this day our daily bread. (LeHeM)

And forgive (MaHaL) us our debts as we also have forgiven our debtors.” Mat. 6. 11-12 TLV

I have often wondered why Yeshua placed the petition for forgiveness toward the middle of His model prayer, after asking for bread. Since childhood, my tendency has been to confess my sin before making petitions. Could it be that bread and forgiveness are linguistically and spiritually linked? I believe the disciples had an Aha moment when they heard these two words connected in Hebrew, a significance lost in the Greek. From a Hebraic perspective, placing forgiveness after bread was strategic. The two words, forgiveness (מחל) and bread (לחם) are a reversal of the same letters. This common Hebrew word play should cause us to ask, “What is the connection between our daily bread and the forgiveness we give to others?”

To illustrate, I will share an old Hebrew riddle of two men, Shimon and Reuben, and a secret message of forgiveness revealed in bread. Shimon sinned against Reuben. Over time the burden of broken relationship was too great to bear. Shimon sent an emissary to Reuben to make peace. Reuben’s reply was most unusual. He sent a platter containing an upside-down loaf of bread. “What sort of message is this?”, thought Shimon, and then he realized the hint (remez) encoded within “bread turned over”, (Lehem hafuk). Bread or LeHeM (לחם) reversed is MaHaL (מחל) – forgiven![1]

Yeshua may have used just such a word play between bread and forgiveness in the prayer He taught His disciples. Franz Delitzsch, who worked tirelessly to place the prayer back into the Hebrew of Yeshua’s day beautifully captured the connection.

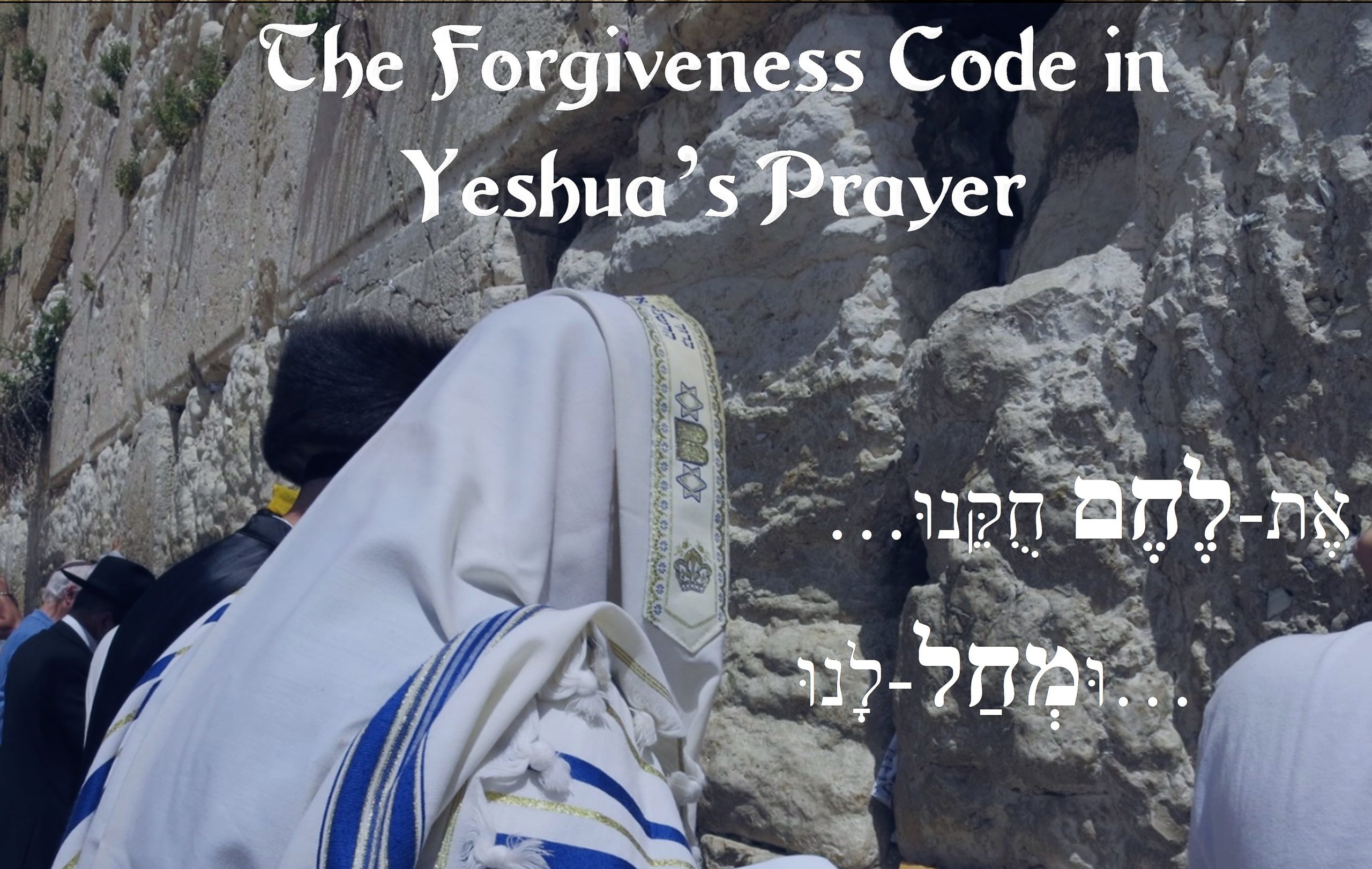

אֶת-לֶחֶם חֻקֵּנוּ תֵּן-לָנוּ הַיּוֹם׃

Give us this day our daily bread. (LeHeM)

וּמְחַל-לָנוּ עַל-חֹבוֹתֵינוּ כַּאֲשֶׁר מָחַלְנוּ גַּם-אֲנַחְנוּ לְחַיָּבֵינוּ׃

And forgive (MaHaL) us our debts as we also have forgiven our debtors.[2]

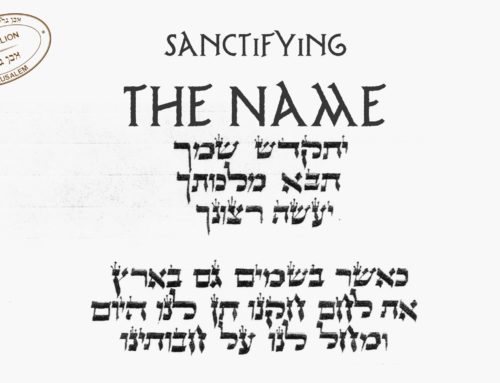

Yeshua’s model prayer is part of His Sermon on the Mount, containing powerful themes of reconciliation, forgiveness, fasting and prayer. Some scholars believe Yeshua taught these during the days of repentance leading up to the Day of Atonement.[3] In Hebrew, there are several words for forgiveness, slichah, mahal, and kaparah.

- Slichah describes forgiveness of sin.

- Mahal is the release or forgiveness of debt.

- Kaparah speaks of covering or atonement.

Assuming Yeshua taught in Hebrew, which word for forgiveness would He have used in His prayer? Textual evidence indicates mahal best fits the prayer.

- Mahal as a word for forgiveness arose during the Second Temple period.[4] Jastrow’s Dictionary of Talmudic and Midrashic literature speaks of mahal as specific to forgiving debt. מחל – machal – “To remit a debt; to forgive, pardon, to forgo, renounce.”[5]

- Professor Delitzsch’s eleventh edition, the culmination of his translation work, translated forgive using “MaHaL”, perhaps because it matched Yeshua’s use of the word debt to describe sin. He was no doubt equally aware of the Hebrew word play between bread and forgiveness.

- An old witness from a Hebrew Gospel also attests to the word mahal. The fourteenth century polemic work “Even Bohan”, by Shem Tob, ben-Isaac, ben-Shaprut, contains a Hebrew Matthew, retaining the word play of mahal and lehem in Yeshua’s prayer.[6]

Like the bread turned over, forgiveness following bread calls us to turn those letters over in our minds to see their richness. The varied combination of those three Hebrew letters, ל.ח.ם, are significant in Jewish literature. They speak of bread (לחם), a symbol of the sacrifice, of salt (מלח), symbolic of covenant, of compassion (חמל), and yes, of forgiveness (מחל). What lessons can we learn from this forgiveness code?

I. לחם – Bread – a Symbol of Forgiveness

Bread and forgiveness are a picture of the “bread and wine” of communion with Messiah. We first see the two paired when Melchizedek, who a type of the Messiah, revealed their significance to Abraham. Gen. 14.18 In the fullness of time, Yeshua, the Messiah revealed Himself as the “bread and wine”, a meal of forgiveness.

“Now while they were eating, Yeshua took matzah; and after He offered the bracha, He broke and gave to the disciples and said, “Take, eat; this is My body.” And He took a cup; and after giving thanks, He gave to them, saying, “Drink from it, all of you; for this is My blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the removal of sins.” Mat. 26. 26-28 TLV

A Rabbinic View of Bread

After the destruction of the Temple, the Sages of Israel saw bread on the table as symbolic of the sacrifice on the altar. Ezekiel even referred to the altar as “the table”.

“The altar was of wood, three cubits high, and its length two cubits. Its corners, its length, and its sides were of wood; and he said to me, “This is the table that is before the Lord.” Ezek. 41.22 NKJV

According to the Sages, inviting the hungry and needy to the table effects atonement.

“Rabbi Yohanan and Rabbi Elazar both said, ‘When the Temple is standing, the altar effects atonement for transgressions of a person, but now that the Temple is not standing, a person’s table effects atonement…’” Bab. T. Menachot 97a[7]

II. מלח – Salt a Symbol of the Covenant

How did the Sages connect bread (לחם) to sacrifices in modern Judaism? Through the sprinkling of salt (מלח). The Hebrew word for salt is another combination of these three letters in the forgiveness code. Our bread symbolizes the grain and meat sacrifices on the altar, which must be sprinkled by a “Covenant of Salt”. [8] Leviticus 2.13

Salt (מלח) is a reminder that we have an enduring, unbreakable covenant with God, but the bread on our table cannot atone for sin. Messiah has invited all to dine at the table of the Lord. And that brings us to a combination of the letters that I will only touch on briefly, compassion (חמל). It is because of His great mercy and compassion that the invitation is given. None of us are deserving; salvation is the gift of God.

III. מחל – The Message of Forgiveness

There is an old Gospel song whose refrain says,

“Come and dine”, the Master calleth, “Come and dine”; You may feast at Jesus’ table all the time; He who fed the multitudes, turned the water into wine, to the hungry calleth now, “Come and dine”.” C.B Windmeyer, 1907

Yeshua’s bread is the ultimate reversal for sin. When turned over, His bread (לחם) reveals forgiveness (מחל). When we pray, “Give us this day our daily bread, and forgive us our debts…”, we petition Heaven to dine at Messiah’s table. Yeshua is the “bread of Heaven”.

“Amen, amen I tell you, he who believes has eternal life. I am the bread of life. Your fathers ate the manna in the desert, yet they died. This is the bread that comes down from heaven, so that one may eat and not die. I am the living bread, which came down from heaven. If anyone eats this bread, he will live forever. This bread is My flesh, which I will give for the life of the world.” John 6. 48-51 TLV

Conclusion

Yeshua likely connected bread and forgiveness in the middle of His great prayer through a Hebrew word play. Through the true bread (לחם) sent by the Father, we find forgiveness (מחל). We pray Father forgive us, as we have forgiven others. The table of the Lord still beckons the hungry to partake the “bread and wine”, atonement through Messiah’s shed blood. But bread and forgiveness are not simply about our need. They call each follower of Messiah to ask, “Who is missing from the table?” Are there friends or family who have not yet partaken of the Lord’s bread of forgiveness? They too should be invited to come and dine at Yeshua’s table! When our family gathers each Friday evening before Sabbath, we break the bread and dip into the salt (מלח) to remind us of the Lord’s eternal sacrifice for sin. I can no longer pray the Lord’s Prayer without thinking of the undeserved mercy (חמל) calling me to His table of forgiveness (מחל) and the bread (לחם) of life found only through His atoning sacrifice. As we approach this season of repentance, I hope to see you also at the Lord’s table.

Shavua Tov, The Staff of Even Gilion

[1] Imrei Binah, Part III; General Riddles, Answers 46:1. (n.d.). Retrieved September 08, 2020, from https://www.sefaria.org.il/Imrei_Binah,_Part_III;_General_Riddles,_Answers.46.1?vhe=Imrei_Binah,_Jerusalem_1908.

[2] Delitzsch, F. (1892). Sifre ha-Berit ha-ḥadashah. Berlin: Printed for the British and Foreign Bible Society by W. Drugelin, Leipzig, Mat. 6. 11-12.

[3] Ford, J Massyngberde (Josephine Massyngberde). 1967. “Yom Kippur and the Matthean Form of the Pater Noster.” Worship 41 (10): 609–19. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rfh&AN=ATLA0000692761&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

[4] על המילה מָחַל. (n.d.). Retrieved September 08, 2020, from https://www.citationmachine.net/apa/cite-a-website/search?q=https://hebrew-academy.org.il/keyword/מָחַל_פועל

[5] Jastrow, M. A Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic literature: With an index of scriptural quotations. Tel Aviv, IL: Publisher not identified, 1972, 761.

[6] Howard, G., & Ṭov, I. S. The Gospel of Matthew according to a primitive Hebrew text. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1987.

[7] Menachot 97a. (n.d.). Retrieved September 08, 2020, from https://www.sefaria.org.il/Menachot.97a?lang=bi

[8] Shulhan Aruch, Sect. 167.8, See also: Leviticus 2.13.

Very interesting comparisons. I pray this prayer daily but now it has more significance of meaning. Wow!