William Bradford – A True Pilgrim’s Progress

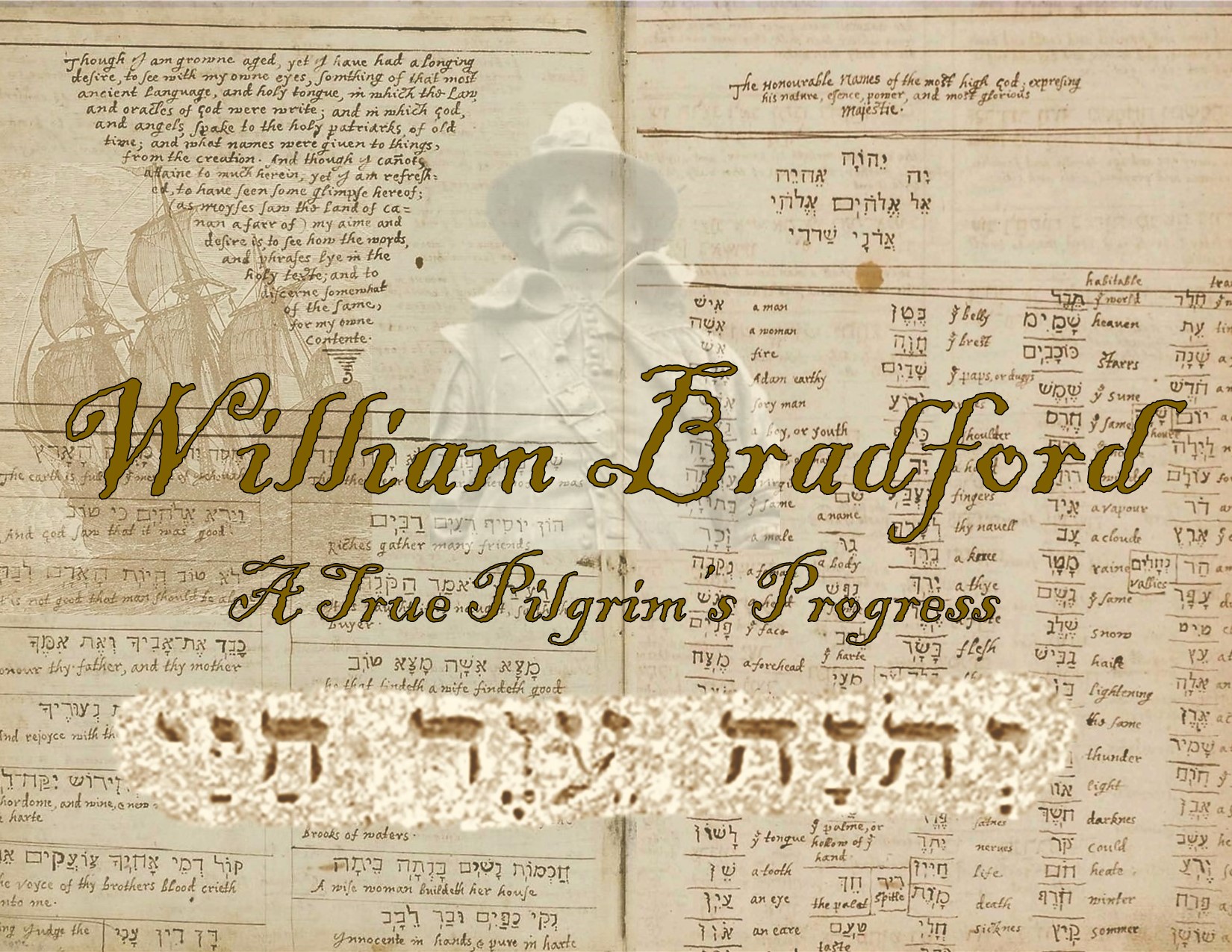

On the coast of Plymouth, Massachusetts, waves lap near a famous rock inscribed “1620”. Not far away, another rock bears a unique Hebrew inscription. It marks the grave of William Bradford, Governor of Plymouth Colony, Pilgrim, and leader of a Christian movement. This year marks the 400th anniversary when Separatist and secular adventurers set out on a voyage of destiny to the New World. This is also the story of how Hebrew to America. In the hold of the Mayflower were more than four-hundred books, many in Hebrew, belonging to the community’s congregational minister, Elder William Brewster.[1] Brewster was not alone in bringing Hebrew. William Bradford’s journal is filled with over a thousand Hebrew words, definitions, and phrases. Was this strictly for his own study or an outline of vocabulary for a new community?

Hebrew came to America in the unlikely form of Christians fleeing a repressive Pharaoh, King James, crossing their Red Sea in search of Zion. Like ancient Israel, they too left their “Egypt”, “a mixed multitude” (Exodus 12. 48), for at the last minute a group of secularists joined them.

Later, descendants of the Separatist and Puritans gave obscure Hebrew names to new settlements such as Boston (orchard), Salem (whole or peace), and Rehoboth (open space). The claim is made, though I have yet to find an original source, that Pilgrims fancied resurrecting Hebrew to replace English in the colony. Sadly, that dream never came to pass, though Puritans did make the study of Hebrew mandatory at Harvard College. Today, Hebrew is making a resurgence among some conservative Christians. Many are moved, like William Bradford, to hear the original voice of the faith.

“Though I am growne aged, yet I have had a longing desire to see with my own eyes, something of that most ancient language, and holy tongue, in which the law and Oracles of God were write; and in which God and angels spake to the holy patriarchs of old time; and what names were given to things from creation…” William Bradford, Governor of Plymouth Colony

As Americans remember the first Thanksgiving, we ask, what parallels from 1620 are being repeated 2020? America, founded on the hopes of religious freedom from inception faced secular challenges to their faith. Bradford’s notebook and Hebrew writings have left a message literally etched in stone. Here are three thoughts for 2020 from the man who brought Hebrew to America.

I. Kadosh, Kadosh, Kadosh (Holy, Holy, Holy)

“Holy, holy, holy, is Jehovah of hosts”, in Hebrew and English, from the notebook of William Bradley.

The thrice “holy” call of angels to the Lord of Hosts in Isaiah 6.3 was penned into the journal of William Bradford. Holy means “set apart”. Separatism characterized the Pilgrims. Unlike the puritans who wished to reform the Church of England from within, Separatists felt the corruptions of the Church of England necessitated leaving. That situation forced them to find a new home, at first in the Netherlands, and then in America. The heartfelt cry of Bradford is echoed among many true believers today. Catholics are questioning the Pope’s unscriptural teachings in greater numbers. Protestants question the secularized church who advocates social issues over Inspired Scripture. Like the Separatists who left the Church of England in 1620, we see a parallel call of holiness and separatism in 2020. Perhaps this is why so many again desire to learn Hebrew. Bradford faced only a few English translations, today we have dozens. The separatist heart says, “take away the veil that I might kiss my bride”.

II. “In Every Age and Age”

Bradley’s translations diverged from the King James at times more literal and accurate.

Bradford recorded these famous words from the book of Esther, a remembrance of the providential preservation of Israel in Persia. Two things are striking. First, Bradford’s translations are unique, literal, and accurate. Compare his translation to the King James text.

“In every age and age, familie and familie, province and province, citie and citie.” Bradford

“Throughout every generation, every family, every province…” Esther 8.9 KJV

Secondly, Bradford copied Hebrew Scripture portions which could easily be spoken in the everyday conversation of a leader or farmer in work or prayer. It may be less a grammar and more of a method to bring the language to life. He translates texts which expressed life in the colony and New World.

“Seed time and harvest, and could and heate, and sommer and winter, and day and night, shall not cease.” Gen. 8.22 W. Bradford

Such a text could easily be adapted to form the Hebrew syntax needed for personal expression. Bradford found his voice in Scripture. He breathed it afresh to a generation facing unprecedented struggle. How does this apply to us in 2020? Our generation too hungers to speak God’s Word. Like Bradford, we must resist those who reinterpret scripture through the out of focus lens of cultural relativism. Bradford was not perfect, nor was his interpretations infallible, but he did attempt to authentically express the faith.

This brings us to Bradford’s most interesting Hebrew inscription, a phrase not found in the Bible. It seems to flow from his own resurrection of the language.

III. “Adonai, the Help of my Life”

“Adonai ezer hayai” (Adonai the help of my life) etched into the obelisk marking Bradford’s grave.

The last Hebrew message from the man who brought Hebrew to America is etched in stone. Hebrew on Jewish New England Colonial headstones is not uncommon. Most, however, are “formulaic”.[2] Bradford’s Headstone contains just three Hebrew words, Adonai ezer hayai (Adonai the help of my life). However, those words do not appear in this combination in either Biblical or Rabbinic literature. Like Eliezer Ben Yehuda who resurrected Hebrew hundreds of years later, Bradford internalized Hebrew to the point of expressing it as a language. The unique construct reveals a grateful heart to the One who led him safely through the sea, delivered him from the King, and gave him grace to lead his flock into the land of promise, some thirty years. His words equally give hope to future generations to put their trust in God.

Conclusion

The Pilgrims of 1620 speak powerfully to the followers of Messiah in 2020. At a time when America should be celebrating the 400th anniversary of the landing at Plymouth Rock, many elites are attempting to mute its memory and importance. The powerful message of the Thanksgiving story is being lost. Pilgrim Separatists persevered within a “mixed multitude” of secularist who also wanted to define who they were. I believe the greatest message from the notebook of William Bradford is to find our voice in the Word of God. No, I am not advocating that we quote King James or even the NIV. I am actually suggesting something more radical. You may not have the ability to study the original languages like Bradford, but Scripture must again become our language, our voice, our very breath. It is not enough to simply be a follower of Yeshua (Jesus) in these last days as vital a first step as that is. We must again internalize and translate His Word and Good News to this present generation – “age and age, family and family, province and province, city and city”.

[1] De Sola Pool, D. “HEBREW LEARNING AMONG THE PURITANS OF NEW ENGLAND PRIOR TO 1700.” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, no. 20 (1911): 31-83. Accessed November 22, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43057875.

[2] Shalom Goldman, God’s Sacred Tongue: Hebrew and the American Imagination (Chapel Hill , N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 126.